War comes to Berlin, August 1940

The late August weather in Berlin was cool for the time of year, but despite the chilly weather, the morale of the Berlin public was high. One year had passed since the Second World War in Europe had begun. Less than a month before the Berlin public had celebrated the return of Germany’s victorious armies, after the fall of France, with a great military parade through the center of the city. With France defeated, many wondered how long the British could go on alone. There was a generalized fear of bombing in many European cities in the 1930s and ’40s, but with a mighty air force (the Luftwaffe) to defend them, Berliners must have felt reasonably safe. Indeed, how could the British, themselves under heavy attack from the Luftwaffe, spare forces to attack Berlin, a city so far from the RAF’s bases in Eastern England?

But attack they did, when on the night of Monday 26th August, a force of thirty Hampden and Whitley bombers found their way to the German capital. The city was covered in thick cloud and British bombs fell over a wide area of the northern suburbs, whilst other bombs fell harmlessly in the countryside south of the city. Very little damage was done. In the suburb of Rosenthal, a garden shed was set on fire and so many bombs fell on farmland that the Berliners joked that the RAF was trying to starve them out. Nevertheless, the fact that the British aircraft had come to Berlin at all was a grave shock. The planes had arrived in several waves, causing the air raid sirens to go off between midnight and 3:30 am. At first, the Berliners had ignored the sirens, but when the anti-aircraft fire began most had scurried to find shelter. Many of them had believed Nazi official propaganda, that an air attack on Berlin was impossible. Herman Goring (commander of the Luftwaffe) had even said that if a single enemy bomber reached the German capital, then his name was not Goring it was “Meyer” (like the English saying “then I’m a Dutchman”).

There had been a few alarms in the previous year, including one when a German plane got lost and wandered over Berlin and cities in the Western part of Germany had been hit by air raids between May and July 1940. Gradually, Berliners became anxious about the future. They had reason to be because the RAF was once again on its way.

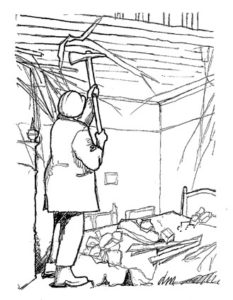

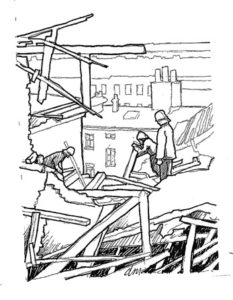

Shortly after midnight on 28th August another British raid appeared over Berlin. A mixed squadron of Wellington and Whitley bombers penetrated the ring of flak defenses on the north and north-west side of the city. Crossing the darkened city center, they arrived over the southern suburb of Kreuzberg. There were no anti-aircraft guns inside the city itself, so the bombers were able to bomb fairly accurately. The streets around the Gorlitzer Railway Station and goods yard were badly hit. Streets were cratered, tram lines broken and twisted and several hundred houses were badly damaged. The fires in the Gorlitzer goods yard were visible all over the city. Ten people were killed that night and two later died in hospital. More than thirty others were injured and nine hundred people were made homeless.

Hitler was furious and saw the attacks as a personal insult. The German press was outraged and denounced the RAF as “bandits” for attacking civilian targets. Of course, the Luftwaffe only bombed military targets when they attacked London! Sightseers came down to Kreuzberg to view the damage. As they gazed on the wrecked houses, many of the spectators must have felt very uneasy about what the future would hold. They certainly knew that the war had entered a new and dangerous phase.

Hitler was further enraged when over three consecutive nights in the following week the RAF came calling again. On the 1st September 1940, he made a speech to Nazi supporters at the Sports Palast: ” And should the Royal Air Force drop two thousand or three thousand or four thousand kilograms of bombs, then we will now drop 150,000; 180,000; 300,000; 400,000; yes one million kilograms in a single night. And should they declare they will greatly increase their attacks on our cities, then we will erase their cities! We will put these nighttime pirates out of business, so help us, God! The hour will come that one of us will break, and it will not be National Socialist Germany.”

Despite the bombast, the people of Berlin felt unable to believe their Government’s promises again. The idea of their inviolable capital city was shattered. The war that Hitler had unleashed a year before had come home.

This is an article from my friend Nicholas Tallentire ( Battle of Britain ), a retired history teacher and historian. The article is illustrated by his friend, Donald Mullis.