Bernard Pietenpol was born in 1901 and lived in the southern Minnesota community of Cherry Grove. From the beginning, Bernard showed an aptitude for all things mechanical and became the town’s “mechanical genius.” Bernard was also intrigued by the new “flying machines” that had gained notoriety and a fair amount of acceptance after WWI.

But flying was expensive, even with all the war surplus “Jennies” and “Standards” on the market. The average aviation enthusiast had a hard time coming up with the cash to buy or maintain an airplane. Bernard, with an eighth-grade education, took it upon himself to build an airplane and teach himself how to fly. He was convinced that airplanes could be powered by automotive engines much cheaper and more available than the expensive certified aircraft engines.

With the help of his father-in-law W.J.Krueger, a wood craftsman, and two friends – Don Finke and Orrin Hoopman, Bernard began experimenting with various wing and fuselage designs, as well as engines to power them. There was a lot of trial and error as Bernard searched for the right combination, always keeping in mind that he wanted to develop an airplane that anyone could afford, construct and enjoy without the expense of factory-supplied special parts or complex construction methods.

Their first attempt, in 1920, was a small biplane which used a Ford Model T engine which was inexpensive and plentiful. Without m\very many alterations, the engine could develop about 20 horsepower but the prototype could not have been called a success. Bernard confessed later, “It would have flown if I’d had known how to fly it. Luckily I didn’t.” Not only did Pietenpol want an airplane that was easy to construct, but it also had to be reasonably easy to fly, since many of those he envisioned flying his airplane would be, like him, novices when it came to piloting skills.

His second project was a similar biplane design using a rotary Gnome engine. This was a step up from the Model T Ford and had a proven track record as it had been used by aviators such as Bleriot in his English Channel crossing and later by Harriet Quimby. The Gnome generated 50 hp, a great improvement, but the engine had reliability problems. After extensive tests, Pietenpol, not pleased with the results, called the Gnome a “growler,” and likely never even flew it. Bernard then decided to try another tactic and bought plans for a Lincoln Sports Biplane from a popular magazine called Modern Mechanics and Inventions Flying Manual published by Fawcett and whose popular aviation writer, E. Weston “Westy” Farmer, was influential in covering the world of “homebuilt aircraft.” By now it was the late 1920’s and successful designs like Edward Heath’s Parasol and O.C. Corben’s Baby Ace was being built both as finished aircraft and in kit form by their companies, and plans were being sold to those confident in their abilities as craftsmen. But these designs required some complex construction skills and equipment to manufacture welds or fabricate intricate control mechanisms that were beyond the scope of the average builder. Of course, these parts could be purchased separately by mail, a practice Pietenpol eventually offered for his designs as well. But the Heath and Corben models also mainly recommended aircraft powerplants which were less available and much more expensive (though each manufacturer did offer plans for using motorcycle engines). Unlike Pietenpol, experimental aircraft designers thought that automobile engines were simply too underpowered. Aviation was still in its infancy in America.

It was about this time that Charles Lindberg flew alone across the Atlantic Ocean inspiring a whole new awakening to the fun, adventure, and romance of aviation. Bernard Pietenpol knew that he had to find some kind of aircraft in which he could gain a bit more flying experience as he kept his dream alive of creating his own design for the “common man.”

Bernard was not pleased with the overall performance of the Lincoln, so he traded it for a Curtiss Jenny powered by the then famous OX-5 water-cooled engine. This was the airplane used by most of the barnstormers who had crisscrossed the Midwest during the decade following World War I and which most observers used as their “yardstick” for comparing the smaller homebuilt airplanes. Bernard logged some hours in the Jenny, but he later admitted that he wasn’t very fond of its quirks, both in the airframe design and its temperamental underpowered V-8 engine.

Meanwhile, Ed Heath’s Parasol was becoming more popular, as well as the kits he sold to builders. If Heath could do it, Bernard reasoned, why couldn’t he? He sold the Jenny and went back to his first instincts, designing and building his own airplane, but, unlike Heath and Corben, designing his airframe around an automobile engine. Bernard Pietenpol sketched up his aircraft design, and with woodworking help from his father-in-law, he and Finke put their workmanship skills together while Hoopman created the post design sketches, later to be transformed into blueprints for sale.

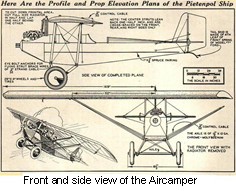

Bernard Pietenpol’s new design, dubbed “ACE,” was a “parasol” type construction – a 27-foot one-piece (initially) high wing placed well above the fuselage, similar to Heath’s Parasol. Unlike the welded tube construction of Heath, Bernard preferred all-wood construction, so the average woodworker could construct his airplane with “usual” skills, which did not include welding. He later offered a steel tube fuselage version of the aircraft as an option.

Bernard Pietenpol moved his workshop into an abandoned Lutheran church in Cherry Grove, MN and worked tirelessly. Finally, on September 1st, 1927, Bernard and Don Finke successes fully flew their new design. It was powered by an aluminum 16-valve Model T engine developed by Horace Keane. At 30 horsepower, it was capable of getting two men into the air and safely back on the ground. It was a step in the right direction, but still, Bernard believed it needed additional power.

By now Henry Ford had come out with his new car, the Model A, powered by a bigger four-cylinder engine. At an estimated 40 horsepower, this engine seemed just the thing for Bernard Pietenpol’s new aircraft design’s needs and had been on the market for several years, junkyards were starting to get as many of them as Model T engines. So Bernard went to work converting the Ford Model A engine for his new monoplane. In May 1929 he test flew his Air Camper with the new engine. It was a complete success – a perfect match of the airframe to the powerplant.

Bernard’s big break occurred in 1930 when aviation editor “Westy” Farmer attended a fly-in at Minneapolis. In previous columns in Modern Mechanics and Inventions Flying Manual, Farmer had declared that he was not a big fan of using automotive engines in aircraft and specifically said that Ford’s Model A engine was not usable at all.

Pietenpol decided to make the flight in his Air Camper up to Minneapolis to prove the editor wrong. In fact, he had Finke fly a second Model A powered airship to the fly-in. Once face-to-face with Farmer, Pietenpol told the crowd, “I believe that this is the safest airplane for the beginner that has ever been built.” He made such an impression on Farmer, and the rest of the crowd, that Modern Mechanics and Inventions Flying Manual published his Air Camper plans serialized in four 1931 issues. That really put Bernard Pietenpol, the Air Camper, and Cherry Grove on the aviation map. Letters arrived in bunches.

| Aircraft Name | Pietenpol Air Camper |

|---|---|

| Specifications | |

| Powerplant | Ford Model A automotive conversion engine, 40 hp (30 kW) |

| Propeller | Wooden |

| Length | 17 ft 8 in |

| Height | 6 ft 6 in |

| Wingspan | 29 ft |

| Wing Area | 135 sq ft |

| Seats | 1 |

| Empty weight | 610 lb |

| Max gross weight | 995 lb |

| Payload w/full fuel | 1080 lb |

| Performance | |

| Rate of climb, sea level | |

| Max level speed, sea level | 100 mph |

| Stall speed | 35 mph |

| Rate of climb | 500 ft/min |

Wings of History T-Shirt Featuring the Pietenpol Air Camper

You can purchase a T-Shirt featuring the Pietenpol Air Camper in our Gift Shop